In 2014, I attended a dinner with friends at the James Beard House in Manhattan featuring an up and coming chef from the South whose name I don’t recall. After a lovely cocktail hour, we were seated at a communal table with 6 other people, two of whom happened to be the parents of the chef, to enjoy a multi-course dinner and food pairing. While I can’t recall a thing from the menu, I distinctly recall the conversation that ensued, one which I have replayed many times over in my head for years since.

The chef’s father sat to my left. At some point during dinner, the topic turned to women’s rights and equality. Two women across the table from me spoke of how far women have come over the past several decades, while at the same time acknowledging there was still much work to be done. At that point, the father of the chef leaned over to me and said in a quiet, somewhat reluctant voice, “I really want to ask a question but I don’t quite know how to.” I looked at him puzzled and said, “Well, just ask it.” After a brief pause, he asked, “But why hasn’t that happened for the blacks?”

I remember experiencing a tidal wave of thoughts and emotions in that brief moment – anger, disbelief, disgust, disappointment and sadness. And yet, the responsibility to somehow make a difference in this man’s perspective on race in America weighed heavily on me. As absurd as the question was, he was genuinely asking me, a woman of color, in what he perceived as a safe space. It was in that moment that I failed.

I did respond. It was just inadequate. I asked him rhetorically how he could expect black Americans to just overcome hundreds of years of enslavement and oppression, much of which still exists today. But I was unable to develop or articulate this argument further. It was in that instance that I recognized that I had neither a deep enough understanding of American history nor did I possess the right language to have the power to influence him.

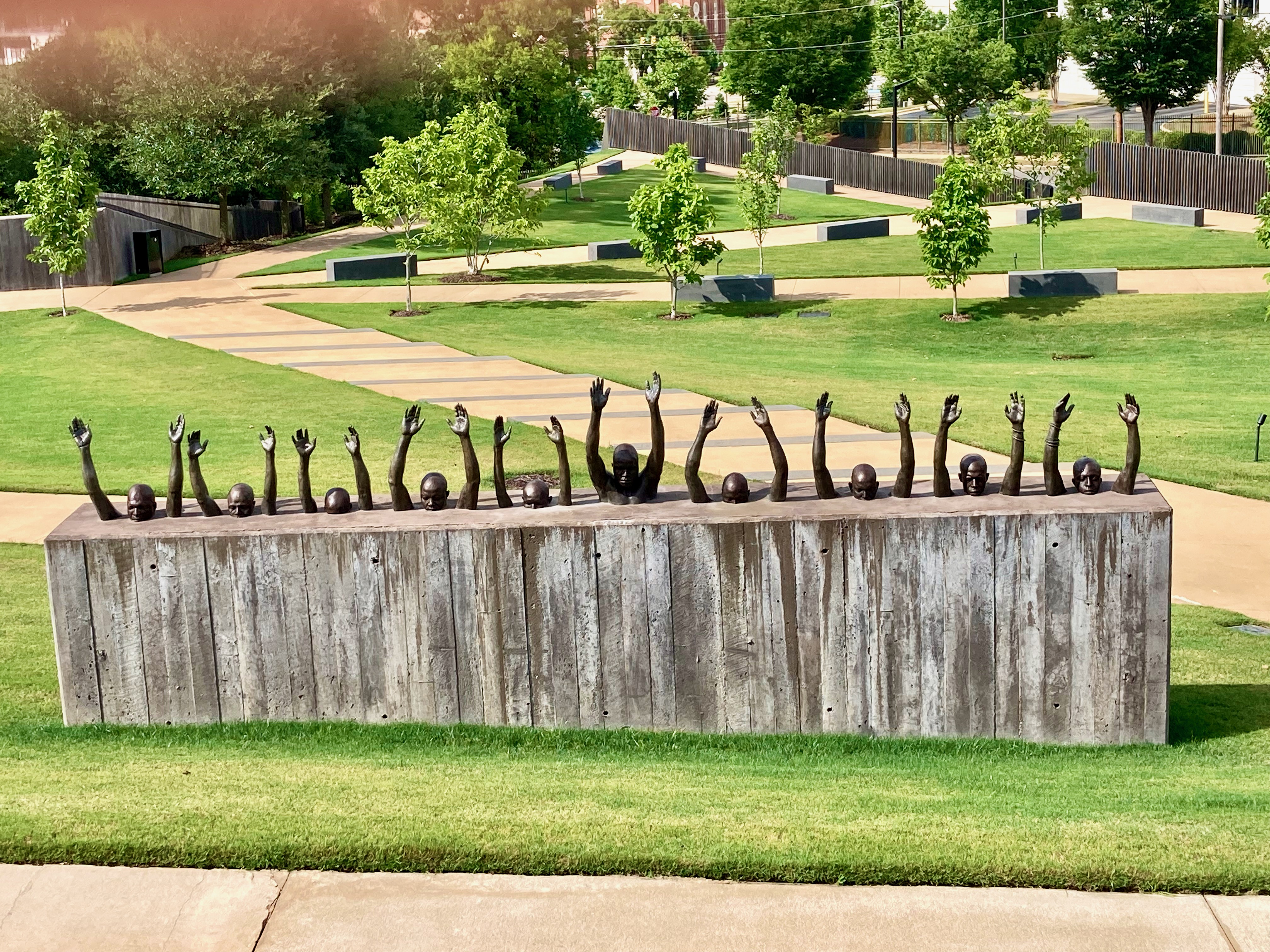

Years later, as part of my commitment to educate myself and read more, I picked up Just Mercy, by Bryan Stevenson, after watching his Ted Talk. That book altered something in me. In his writings, Stevenson, a graduate of Harvard Law, describes his relentless crusade against capital punishment and mass incarceration in America, highlighting the vast inequities in our justice system that disproportionately affect people of color both historically and today. He details his successes and failures in each gut-wrenching story of his wrongfully accused clients, mostly black men on death row. In 1989, Stevenson started the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), a 501 (c) (3) non profit organization committed to systematically dismantling these inequities and shifting the narrative in America. In 2012, it was Stevenson who argued and won the Supreme Court case banning life sentences for children under 17 without parole in the US. Take a moment to absorb that – just 9 years ago, we were sentencing children to life in prison without parole. In 2018, EJI opened America’s first Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration and National Memorial for Peace and Justice documenting the evolution of slavery to present day injustices and to commemorate the thousands of black lives erased by racial terror lynchings in America.

It was Stevenson’s work that propelled me to seek to understand the roots of the inequities in our country and globally, the desensitization to it and rationalization of it. I needed to learn the language so that I could somehow become part of changing it on whatever scale possible. That need influenced my decision to take the year off in 2018 and explore the world through this intentional lens. I documented my observations and experiences around equity in blog posts during my time abroad and upon returning home. I set a record of reading 15 books that year, mostly centered around the topic of social justice. I set out to do the work of learning what I was never taught in a classroom.

Three years and a global pandemic later, I decided to go on a civil rights driving tour of the South along with a small group of friends. EJI was at the top of the list! We arrived in Atlanta, picked up a car and made stops in Montgomery, AL, Selma, AL, Jackson, MI, and New Orleans, LA. I decided to write about my learnings in the hopes that it will inspire others to not only seek a deeper understanding of our country’s history, but also to become part of the fabric of change moving forward.

Our first stop was the EJI National Memorial for Peace and Justice and the Legacy Museum in Montgomery. Downtown Montgomery was home to one of the largest domestic slave trading centers in the antebellum south. Located in an old slave warehouse, it’s no surprise this was the chosen site for the museum. While the two to three hour self-guided tour through the museum is filled with lessons on the consequences of valuing wealth above all else, the moral rationalization of evil and the brutality of man, this alone is an incomplete story. Most noteworthy was how the narrative centered masterfully on the strength and resilience of the oppressed and the remarkable individuals and communities who stood up to injustice, each time risking their lives and the lives of their families. With regards to the National Memorial commemorating the thousands of lives taken by terror lynchings in the American South, it’s impossible to put the visceral emotion it evokes into words. It’s well worth the trip so you’ll just have to experience it yourself.

On the way to Jackson, MS, we stopped in Selma to walk across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, an unassuming 250-foot bridge notable as the location of the brutal Bloody Sunday police attack on peaceful civil rights protesters marching for African Americans’ right to vote on March 7, 1965. Bloody Sunday is believed to have been a tipping point in the civil rights movement. The bridge, we learned, was named in May of 1940 after Edmund Pettus, a former US senator, lawyer and a statesman. He also happened to be a leader in the Klu Klux Klan. We stopped in a modest souvenir shop and struck up a conversation with the employee – a young black man who moved to Alabama from San Francisco to work as a nonviolence trainer. He shared that people are divided on renaming the bridge and that there are, in fact, some who were among the original protestors or are relatives of those who marched on Bloody Sunday who feel that renaming the bridge would be erasing everything they fought for that day. Others who are opposed simply cling to the racist ideals of the old South.

From Selma we made our way to Jackson to visit the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, which showcases eight interactive galleries uniquely curated to highlight pivotal figures like Medgar Evers and events that propelled the civil rights movement in Mississippi. The narrative is unapologetically honest yet hopeful. Jackson is a city of less than 200,000 people and, as our waitress at dinner that night informed us, is pretty much the only liberal city in the state of Mississippi. Though, on an early morning run, I stumbled upon a confederate cemetery right smack in the middle of this liberal city. As I ran through the neighborhood, I noticed the signs of economic depravity – rundown homes and minimal car traffic. On my way back to the hotel, I took note of a large lawn sign advertising a black Mayoral candidate, Chokwe Antar Lumumba. My bias kicked in immediately and I made the assumption that it would be a far reach for a black man to win in this city. Turns out I was wildly off base. Lumumba won the race by 69.3% of the votes. It also turns out that Jackson is nearly 80% black and only about 16.5% white.

There were numerous lessons I absorbed during our journey from Montgomery to Selma to Jackson. Below are some of the most noteworthy insights that both deepened and shaped my understanding of African American (a.k.a. American) history.

- In 1807, Congress abolished the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. Domestic slave trade was unaffected and in fact continued to flourish. By this time there were over four million enslaved people in the south. Domestic slavery was the primary driver of Southern wealth by way of the cotton fields.

- The real hero in the story of slavery’s demise is Frederick Douglas. The Emancipation Proclamation, declaring an end to slavery, was issued on January 1, 1863 but it was not until the end of the Civil War with the passage of the 13th Amendment in July of 1865 that nearly all slaves were finally freed. Abraham Lincoln is classically portrayed as the altruistic hero who ended slavery in this great American narrative. What’s not discussed is that he held long standing segregationist views and did not want freed slaves to remain in America. In fact, at one point, he had plans to banish them to an island off the coast of Haiti. It was the powerful and steady influence of his friend Frederick Douglas who helped shift his perspective.

- Reparations were always part of the plan. The famous “40 acres and a mule” was a promise made to all freed slaves. When Lincoln was assassinated, Andrew Johnson, a notorious sympathizer of the South, rescinded that promise. Over four hundred years later, as we continue to discuss and debate the topic of reparations, we see the glaring effects of this devastating decision in the racial wealth divide throughout our country.

- The end to slavery devastated Southern slaveholders and posed a major threat to their vast wealth. They needed to get creative to preserve it. This led to the beginning of a new era of mass incarceration through exploitation of a loophole in the 13th Amendment which abolished slavery except in the cases of prisoners convicted of crimes. Enter an explosion of falsely accused black men, women and children. Convict leasing flourished in the South, a legacy that still plays out in various forms today.

- Following the passage of the 13th Amendment, a surge of Black codes were passed across the states severely limiting the rights of black people. These limitations included what jobs could be held, the ability to leave a job once hired and the type of property that could be owned. These codes paved the way for the Jim Crow laws in years to come.

- Racial terror lynchings were spectator sports in America akin to carnivals. In her book, Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, arguably the most profound piece of literature I’ve ever read, Isabel Wilkerson painstakingly describes how newspapers advertised upcoming lynchings, schools would be let out early so that families could attend with their children and thousands, sometimes tens of thousands, would gather with excitement in anticipation of watching the brutal murder of a black person. Lynching postcards with photographs of hanged men were popular forms of celebration documenting these grotesque public spectacles by the turn of the 20th century. More than 4,000 African Americans were murdered by lynching between 1877 and 1950.

- The Montgomery Bus Boycott is a remarkable story of black feminism and the power the people hold as a collective. A few months before Rosa Parks, Claudette Colvin refused to give up her seat on the bus and was arrested for it. Parks, Colvin and others began organizing the boycott. Its success is attributed to the Women’s Political Council (WPC), a black activist organization that widely publicized the boycott. The result was an eleven month boycott of the public bus system by over 40,000 people, the majority of the city’s riders, many of whom walked upwards of 10 miles a day to and from work for almost a year. Now that’s grit.

Above all, it’s imperative that we recognize that most of these injustices throughout history didn’t just vanish as many would like to believe, as the story is told in our textbooks. But rather they morphed into more subtle, silent versions. Versions that are easily rationalized by humans, a convenient skill our species has mastered for thousands of years. Mass incarceration, capital punishment, the school to prison pipeline, the privatization of American prisons, underfunded public schools, police violence and brutality, unjust housing practices (mortgage lender denial rates 80% higher for blacks), racial health disparities, redistricting, voter suppression in communities of color – all of these are the byproducts of a very old and intentional system.

Thinking back on my limited education about African American history in school, the focus was never on the unwavering courage to endure life as abusive as it was, the resilience of a chronically disenfranchised people or the heroism and sacrifices so many made for the good of the whole. These are the stories that need to be told.

We ended our Southern tour in New Orleans, meant to be the lighter part of the trip. Despite being one of my favorite cities in the US, I found myself struggling to appreciate it as I normally would have on past visits. As I took note of the beautiful old, ornate architecture, grandiose homes on Magazine Street and thriving businesses, the racial wealth divide was staring fiercely back at me. Few, if any, people of color owned these properties. Hundreds of years later, such prosperity remains out of reach for the many generations of those who created that wealth.

When I think back to that dinner at the James Beard House seven years ago, I do feel better equipped to have the conversation today. It’s uncomfortable to look within and to engage in discussions about race in America. But with discomfort comes growth. It’s only through acknowledgement and validation of the past can we move forward – more evolved, more human.

Book Recommendations:

- Just Mercy by Bryan Stevenson

- Caste by Isabelle Wilkerson

- The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabelle Wilkerson

- How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi

- American Prison by Shane Bauer

- Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehesi Coates

- Heavy by Kiese Laymon

- The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander

- Tangled Up in Blue by Rosa Brooks

- Stamped from the Beginning by Ibram X. Kendi

- White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo

Noteworthy Documentaries:

- Thirteen on Netflix

- Amend on Netflix

- Explained, Episode 1: The Racial Wealth Gap on Netflix